Maigne’s syndrome is a low back disorder that affects the area of the spine that connects the lumbar and thoracic regions (the thoracolumbar junction). Named after the French doctor, Robert Maigne, who first identified the disorder. The condition is also known as thoracolumbar junction (TLJ) syndrome, lumbodorsal syndrome, and posterior ramus syndrome. Maigne’s Syndrome is believed to be a relatively common spinal disorder, especially in people who have back pain or dysfunction, and it is often overlooked by GPs and other clinicians. For this reason, it is impossible to say exactly how many people are affected by the condition.

Referred Pain:

- With Maigne’s syndrome, the most common symptoms include:

- Pain in the lower back region, typically around the SI joint

- Pain in the groin or genitals

- Lower abdominal pain

- Pain in the pubic bone

- Pain in the lumbo-sacral region

Anatomy of the TLJ:

- The thoracolumbar junction is anatomically defined as the joint between the 12th thoracic vertebra (T12) and the first lumbar vertebra (L1); it would, therefore, be described as T12-L1.

- However, while the majority of the stress may be borne by the facet joints between T12-L1, in reality, any spinal joints between T9-L2 have the potential to become dysfunctional, inflamed, or develop lesions and nerve impingements, further increasing the risk of referred pain.

- The structure and function of these adjacent spinal regions do differ somewhat; the lumbar spine, for example, has almost no rotational ability, while the thoracic spine is able to rotate because the facet joints in this segment are aligned more in the frontal plane, as opposed to those in the lumbar spine, which are aligned more sagittally.

- It is well documented that the 11th, and 12th thoracic and the 1st lumbar vertebrae are the most common sites for spinal trauma.

- When the rotational force (torque) from the thoracic spine passes through into the lumbar vertebrae, as would be the case during many twisting and turning actions, the surrounding tissues must absorb this force to protect the lumbar spine from also twisting or rotating.

- The more times these motions are repeated, especially under load, the greater the risk of irritation and inflammation in the surrounding spinal structures. Slouched sitting postures, especially when sustained for long periods of time, also impose greater loads on this area and as such increase the potential for dysfunction.

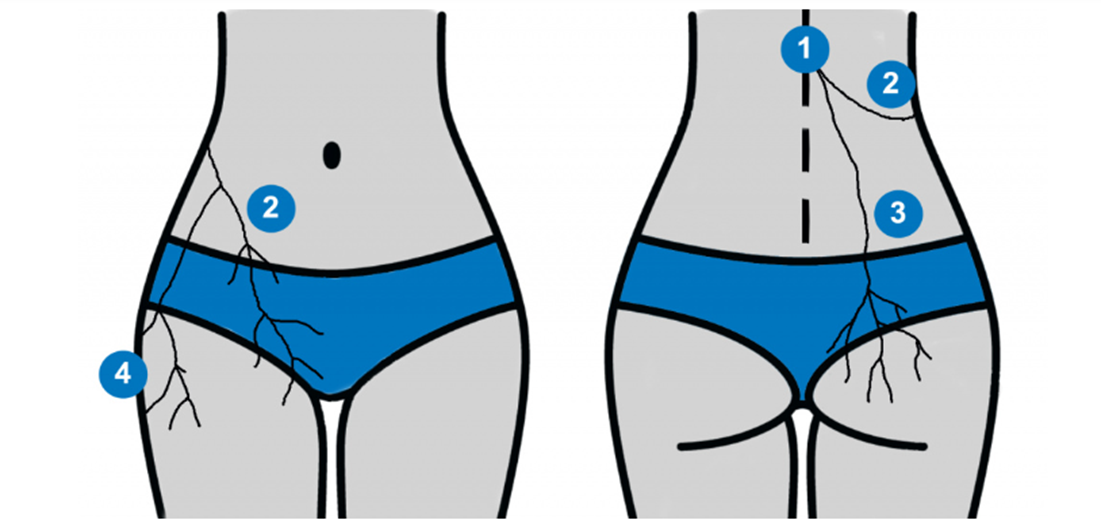

The primary groups of nerves exiting the TLJ include the anterior ramus, posterior ramus, and the perforating lateral cutaneous branch. Figure 1 (below) shows the distribution of these nerve groups and illustrates the common pathways that pain is often referred to in those suffering from TLJ syndrome.

In the above image, (1) thoracolumbar junction, (2), pain being referred into the inguinal and groin region, (3) into the gluteal and sacroiliac region, and (4) into the outer thigh region.

Cause of Pain in Maigne’s Syndrome:

- The primary pain mechanisms in Maigne’s syndrome are the irritation of the thoracolumbar posterior ramus, inflammation, and degeneration of the facet arthritis in and around the thoracolumbar junction (anywhere between T9-L2), disruption to the intervertebral disc in the thoracolumbar region, and/or other degenerative processes.

Differential diagnosis:

Musculoskeletal differentials:

include anterior or posterior spinal nerve compromise at the T/L junction, lumbar zygapophyseal joint dysfunction, disc disruption, congenital malformations, degenerative disc disease, and fibromyalgia.

Non-musculoskeletal differentials:

include spinal tumors, renal disease, neurofibroma, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and inflammatory processes.

Diagnostic Criteria:

There are 4 diagnostic criteria used to identify Maigne’s syndrome. A positive diagnosis can be made with any combination of the following criteria:

- Pain in the lower back, sacroiliac, groin, genitals, outer thigh, and lower abdominal region(s)

- The pain is usually unilateral (one side), although bilateral (both sides) cases have been known to occur. The pain is chronic and constant, although it may vary in severity. It can usually be provoked on examination by palpating the facet joints.

- Imaging rarely helps in finding a definitive cause of the pain. Where degeneration is found, this can often lead to false diagnoses and/or unnecessary surgery.

- Pain is relieved by the injection of a local anesthetic into the offending tissues. It is this criterion that often convinces clinicians of the diagnosis, although there is naturally a lot of reluctance from clinicians to perform the procedure without a definitive diagnosis. This represents a significant clinical dilemma.

Examination:

Tenderness of palpation of the TLJ, the iliac crest should be palpated for tenderness. Move 7 centimeters laterally from the midline and rub the crest in an up-and-down motion on the posterior iliac crest point. This should elicit sharp pain as the irritated cutaneous branches of T11-L1 are compressed.

Kibler Fold Test:

- In the Kibler Fold Test, the examiner raises a fold of skin between the thumb and forefinger and rolls it along the trunk perpendicular to the course of dermatomes. The patient should experience more tenderness and hyperesthesia on the affected side compared to the healthy one.

Rehab protocol:

Patient education can be used to encourage patients to avoid aggravating postures, mainly cervical extension, thoracic spine extension, and hip flexion, which will prevent re-injury. Passive treatment of T/L syndrome includes a thoracolumbar extension in a supine position (described as a thoracic anterior manipulation at the T/L junction). Prone mobilizations at the thoracolumbar junction may also be used.

Phases of Rehab:

A plan of management can be divided into a 4-phase functional restoration program:

Phase 1: Decrease pain and inflammation – ice, electrical stimulation, NSAIDs, postural education, myofascial therapy

Phase 2: Restore range of motion – muscle balancing (eccentric strengthening of transverses abdominus to control thoracolumbar trunk rotation, multifidus to control extension), flexibility, manual therapy (restoration of hypomobile segment), dissociative movement therapy, elementary stabilization, gait mechanics.

Phase 3: Improve strength and stability – intermediate and advanced stabilizations, proprioceptive retraining, dissociative movement therapy, plyometrics, and weight training.

Phase 4: Return to work/ play – task specific

Exercises:

Generally, thoracic mobility exercises can be used to improve the upper back’s active range of motion. By improving the mobility of restricted regions you may be able to offload compensatory stresses applied at the thoracolumbar junction. An example of a thoracic mobility exercise is the THORACIC ROTATION EXERCISES.

Dissociative movement exercises may also be used to offload the thoracolumbar junction. Dissociative exercises aim to improve your ability to isolate movement in one region from an adjacent region. With this condition, an exercise may involve moving the lumbar spine independently from the thoracic spine or vice-versa. An example of a dissociative exercise for the T/L junction is the SPLIT SQUAT PELVIC TILT.

Stability exercise may be used to reduce thoracolumbar hyperextension which will reduce re-aggravation of your symptoms. The goal of stability exercises is to improve your ability to hold a neutral spine (anti-rotation, anti-extension) to reduce the likelihood of falling into an extension pattern when fatigued. An example of a stability exercise is the BEAR CRAWL ARM LIFT.